During the early summer of 2014, the Philharmonia Orchestra was in the midst of simultaneous projects all aimed at different audiences in different geographies. Any one of these would have taxed the average staff to the limits. For the Philharmonia, it seemed more like business as usual.

For starters, the Orchestra and its Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor Esa Pekka Salonen were closing the ensemble’s season at the Royal Festival Hall in London with Mahler’s 8th Symphony and all the logistics that go with the over-sized orchestra, choirs, soloists, and organ that the “Symphony of a Thousand” requires. It was the final concert in a demanding week of rehearsals and performances that included a Salonen-led world premiere by Kaija Saariaho on a program also featuring works by Sibelius, and a film music concert titled Screen Heroes, conducted by Carl Davis.

Meanwhile, the Philharmonia’s iOrchestra three-month residency in southwest England was in full swing, connecting the organization and its musicians with people living in rural Cornwall, Plymouth, and Torbay. Here, the Philharmonia sought to build a new, durable network of local music organizations, educators, and musicians, bringing digital immersion experiences and live concerts by the world-renowned ensemble to people and places they’re seldom available.

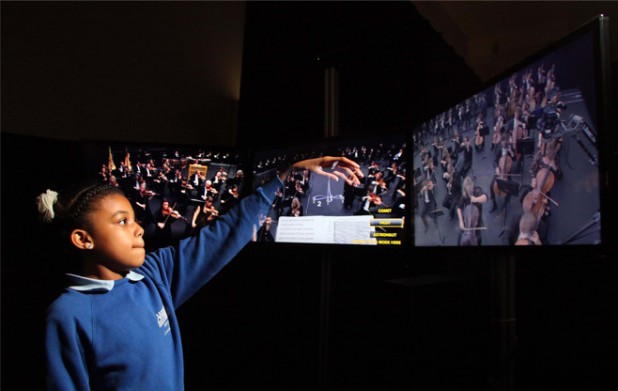

iOrchestra is the latest in the Philharmonia’s ambitious series of digital media projects. It has two main components. MusicLab is a pop-up digital installation built inside a 40-foot trailer that delivers hands-on music education activities for children, schools, and families. For the 2014 residency, the Philharmonia’s education staff toured with MusicLab to bring musical discovery programs to rural Cornish villages, housing estates and inner-city communities. The Philharmonia also arranged to install re-rite in the region’s three major metropolitan centers: Plymouth, Truro, and Torquay. A large-scale, walk-through media installation – large enough to fill a public square – re-rite gives its visitors the experience of being seated within the orchestra during a live performance of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

Founded after World War II in 1945, the Philharmonia lays claim as the UK’s national orchestra because it performs across the country, including current residencies in Leicester, Bedford, Basingstoke, Three Choirs Festival, and Canterbury in addition to its 35-concert residency at London’s Southbank Centre. The Philharmonia ranks among the world’s most recorded orchestras, founded in part to build a legacy of symphonic music for wide public distribution. The Orchestra continues to create recordings for traditional media (CDs) through its partnership with Signum Records, to broadcast concerts on radio and the Internet on BBC Radio 3 and with ClassicFM, and to record soundtracks for films and video games. Beyond traditional concerts across the UK and its recordings and broadcasts, the Philharmonia tours globally many weeks annually. It also has collaborated for decades with leading conductors, soloists, and composers.

The Orchestra’s traditional concerts, classical recordings, and soundtracks are just the beginning of the Philharmonia’s diverse musical menu. Esa-Pekka Salonen, an eager ensemble of musicians who share management responsibility with administrative staff, and a talented team of digital producers have united to create one of the most adventurous new media efforts of any cultural organization today. The eight-person digital department reports directly to Managing Director David Whelton, scheduled to retire in June 2016 after 29 years with the orchestra. It serves the entire organization by working with leaders of the concerts, education, development, and marketing groups. Whelton says the Philharmonia has learned that these projects “are a way to transform the orchestra and its relationship to its audiences.” Musicians are behind these initiatives fully, even voting to donate some of their time to them.

A shared conviction that audiences are curious about and will enjoy experiencing what it’s like to be in an orchestra has framed the Philharmonia’s digital strategy. In a 2006 project called Play Orchestra, chair-sized colored blocks were placed in an orchestral configuration and activated recorded orchestral instruments when people sat down. If two people sat on separate chairs, they “played” together as separate instruments in a larger ensemble. As some people did this, others saw what was happening. They joined in, enlarging the orchestral group. To hear the entire piece, all 58 seats had to be filled. This playful installation encouraged the Philharmonia to continue to experiment with ways to create a more deeply felt orchestral experience. “Most people know nothing about what we do,” Whelton says. “This project began to open that window in new ways.”

Since creating the Play Orchestra, the Philharmonia has developed its “be the orchestra” idea in multiple projects. For re-rite (The Rite of Spring) and then Universe of Sound (Holst’s, The Planets) the Orchestra was recorded on multiple video cameras assigned to instrumental sections. Then individual section’s films were dispersed in an array of rooms, projected at larger-than-life scale. Audiences walking around the rooms can hear the full orchestra performance from the different sections, conduct the piece on camera, and even play along by bringing their instruments and reading from scores placed throughout the installation. Both re-rite and Universe of Sound have toured with the orchestra, opening up new dimensions of community engagement that Philharmonia officials believe have expanded its competitiveness internationally. At a time when touring is constrained for some orchestras, the Philharmonia has kept pace partly by broadening residencies to include these digital components. More than 100,000 people have experienced them in London and elsewhere, but they have yet to come to the United States.

The Philharmonia also created an iPad application, Orchestra, an ambitious exploration of each orchestral instrument as explained and demonstrated by the Philharmonia’s musicians. The app offers multiple performances of ancient and contemporary works, with full scores and commentary (audible or sub-titled) by Salonen and musicians. The paid app had been downloaded 30,000 times by August 2014. It has reached the break-even point in production expense.

The Philharmonia regularly produces videos to document its projects, provide audiences with information about works it’s performing, and offer behind-the-scenes views (the Orchestra’s YouTube channel hosts more than 300 videos). Esa-Pekka Salonen’s own curiosity about all-things-digital was amplified in an advertisement for Apple that went viral. The ad shows Salonen, a composer as well as a conductor, using his iPad to create his Violin Concerto.

Reflecting on the work, Whelton says that, “Our best ideas come from a spirit of experiment. They evolve from something to something with an experimental quality. You have to be prepared to go with the risk and understand that you’ll learn and refine.” He went on to say that the immersive nature of the large-scale digital installations has “brought people together who wouldn’t normally be together,” and stretched the organization to think about audiences in new ways. With new pathways into the experience, and an open invitation to participate, many more people can be interested in orchestral music.

Asked about lessons learned, a roundtable of the Philharmonia staff suggested these. Never compromise on quality, ever. Look at what other people are doing, be curious about it and learn from it. Pay attention to data, listen and adapt to audience responses. Keep it fun. And do your work with huge amounts of love.