The Cleveland Museum of Art celebrated its centennial year in 2016. To prepare for its second century, the Museum recently completed a $320 million, 8-year renovation and expansion project that added exhibition space; renovated existing classrooms, lecture and performance halls; and built the expansive glass-enclosed Ames Family Atrium for public events (at 39,000 square feet, it is Cleveland’s largest open public space, and includes free wi-fi access). With leadership from pre-eminent architect Rafael Vinoly, the newly-reopened building asserts the Museum’s place as a cultural beacon for northeast Ohio and provides extraordinary convening space for community engagement and public assembly for the entire city.

Physical assets were not the only things the Museum was working on during the renovation. Leaders saw the Museum’s physical transformation as an opportunity to activate its digital media strategy and to create a visitor experience unique in the museum world. The results are visible in Gallery One, a new interactive exhibition space at the Museum’s entrance; in ArtLens, the Museum’s mobile application designed to help visitors explore specific works of art on display; and in the robust digital asset management system built to support both these projects and future initiatives.

The Museum’s “build once, use everywhere” digital infrastructure design required deep consideration of all the ways the digitized collection might some day be linked, explored, and used both across the Museum’s departments and by the public. CIO Jane Alexander, who led the information architecture planning process, says in her published paper about the work that the Museum’s strategy was developed to allow many and multiple uses of a single, comprehensive digital architecture. The key to providing more and better digital access to the Museum’s artworks was to build a single platform for storing, managing, and publishing information about the collection. Alexander’s singular department provides the staff structure not only to digitize the collection efficiently but also to support all digital initiatives across the organization.

In Gallery One, visitors enter a large exhibition space filled with works of art, and also embedded with highly interactive technology. For example, a column excavated from an ancient temple was on display in 2014. Touch the nearby screen, and a photo of the excavation site appeared showing the original function and placement of the object. At another screen, visitors could “make a face” into a camera, and pictures of artworks from the Museum’s permanent collection with similar facial expressions immediately populated the screen. While examining a tapestry, visitors could touch a screen to learn about the multiple narratives told in the stitchery. And in Studio Play you could play a variety of interactive games, including drawing a shape on a touchscreen and seeing an artwork with a similar shape appear.

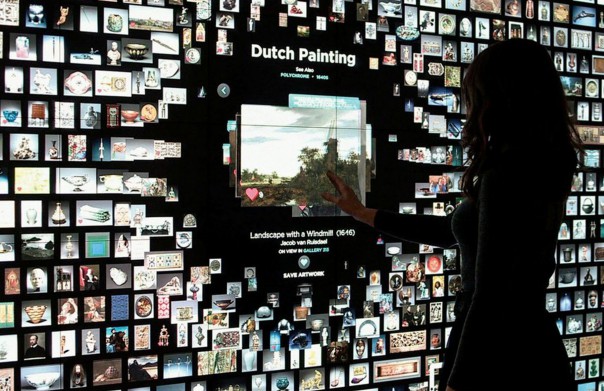

These interactive experiences are illuminating and fun, but the technological marvel in Gallery One is the Collection Wall, a remarkable 40-foot touchscreen developed by the museum staff and a cohort of consultants. The largest screen of its kind built at the time, it alternates between displaying all 4,200+ artworks viewable in the museum’s galleries (each about the size of a playing card) and showing larger images grouped thematically by time period, visual theme, or medium. The themes change frequently (they’re on-screen for less than a minute) so the wall seems in constant motion. Standing before it, the visitor can touch a work of art and information appears about its gallery location, provenance, artist, and medium. By marking the work as a favorite, visitors can add it to their phone or tablet using the ArtLens app.

And ArtLens? The free mobile app is available for iPad, and for both IOS and Android mobile devices, and is designed to provide access to the Museum’s collection inside the galleries and at home. By scanning selected works on display, visitors can access layers of interpretive content like related works, video interviews with curators, artists’ biographies, and descriptions of the techniques employed. Artworks can be saved to the visitor’s device, viewed later, or combined with other saved works to create a personalized tour, supported by 242 Bluetooth iBeacons that pinpoint a visitor’s location within the museum. These tours can be uploaded and shared with other app users. About 1,700 people have done so to date, creating tours like, “Mr. G’s Too Fab Asian Tour” and “Kate’s Rockin Party.” Works “favorited” by ArtLens users aggregate continuously, and result in an ever-changing Top Ten list that displays on the Collection Wall in Gallery One.

Curators and staff also have created customized thematic tours of various lengths, most about 30 minutes, and some with video content. ArtLens offers a particularly helpful map, highly detailed, that enables visitors to locate specific works and find other art situated near them. To learn about ways people are using the app, researchers have asked more than 1,000 visitors about the ArtLens experience and recorded their answers on audio- and videotape. Among the comments: “This app feels like having a teacher in your pocket.”

Cleveland’s objectives include using technology to enhance the visitor experience and to encourage repeat visits. When initially creating the ArtLens app, the Museum invested most deeply in innovations the staff believed would serve the over half a million people who visit annually (visitors during the 2016 fiscal year reached 705,000). “In the beginning, we focused on visitors and their relationship to the Museum, ” said Alexander. However, the new mobile version of the app incorporates adjustments in usability for people who hadn’t considered visiting; the Museum saw that many of its digital audience members lived in other regions and countries, for example.

Since the grand re-opening of the Museum complex in 2013, attendance has increased, and is now at a high for the past decade. The ArtLens app has been downloaded almost 76,500 times since launch. Thirty-nine percent of visitors go to the Museum more than four times per year, a key Museum metric. While the Museum cannot document causation between the digital initiatives and increased attendance, use of what’s been built online is increasing alongside attendance.

The Museum’s investment in it digital infrastructure was made possible in part by a $10 million grant from the Maltz Foundation, a Cleveland-based philanthropy, for Gallery One. Like other innovations, the Museum’s recent initiatives were possible only because of these special, restricted dollars. Managers, now faced with bringing costs of digital development and operations into the annual budget, are dealing with this challenge partly by spending less on non-digital categories. Also helping: a marked increase in memberships and donations since the grand re-opening.

Interest in the Museum’s leadership digital projects is high. Alexander and her colleagues speak regularly at conferences and dozens of curious museum professionals visit almost daily from global locations. Key questions for Alexander and the Museum as they move forward focus on the visitor’s technology experience and how it can be enhanced. “The technology has to work really well,” says Alexander. “People live in a digital world today and you have to account for that expectation. We aim to match or hopefully exceed the experiences they can have elsewhere, so that they choose to explore and engage with art.”

Profile Links:

- Transforming the Art Museum Experience: Gallery One, Jane Alexander Museums and the Web 2013

- Gallery One, the First Year: Sustainability, Evaluation Process, and a New Smart Phone App Museums and the Web 2014, Jane Alexander

- Museums and the Web conference papers September 2013 sessions at the Cleveland Museum of Art

- Technology That Serves to Enhance, Not Distract, NY Times, March 20, 2013, Fred A. Bernstein

- WSJ Story on iBeacons at CMA

- Augmented Reality & Kinect